Postmortem: My Participation in The GMTK Game Jam 2025

Posted: 2025-08-16

Updated: 2026-01-25 (wording)

This year, I decided to participate in a game jam. Fortunately for me, the annual GMTK Game Jam was just a few months away. GMTK is a YouTube channel devoted to gamedev topics and each year, they organize a game jam, bringing together hobbyists across the globe to bash out what they can in just 4 days and then enjoy each other’s creations.

For a while, I’ve been on-and-off trying to make games of my own, but found my motivation lacking. I can’t help that making games alone in a corner can feel so pointless. Years ago, I participated in Ludum Dare 40. I remember that time pressure and being part of an event made me very productive, so I wanted to repeat the experience. My goals were modest - I just wanted to put in the effort into making a game, regardless of how it turned out. I can confidently say I did at least that much. You can play the game on itch.io and browse the C++ code on GitHub. Lower your expectations and all that…

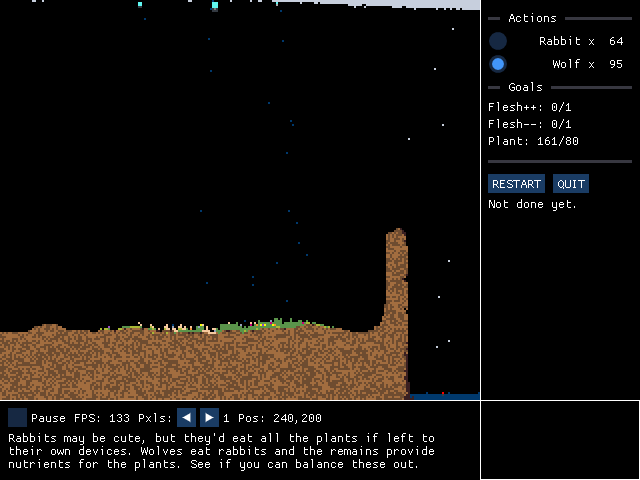

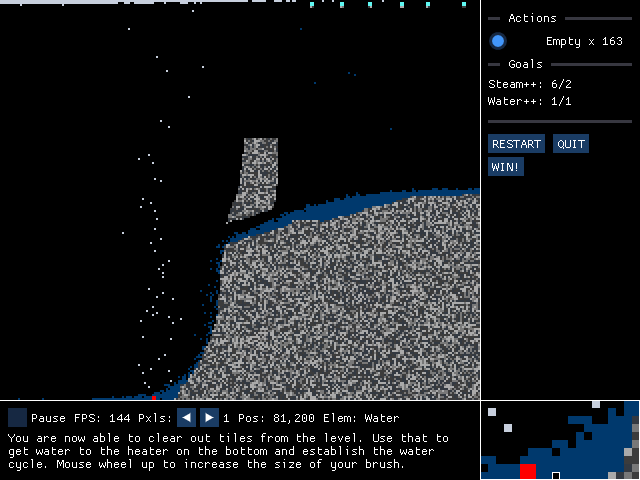

Each GMTK Game Jam has a theme and this year’s theme was simple: LOOP. I drafted a few ideas, but settled on a falling sand puzzler about establishing the water cycle in each level. A cycle is kind of a loop, right? I liked the idea because it would be mainly about coding, which I know how to do, and not require drawing sprites.

I watched a few videos about falling sand games (here and here) that showcased some considerations that need to be made (eg. how water falls and how it disperses). There are also good free examples online that I consulted, like this one and this other one. Eventually, I added plants, rabbits, and wolves to make a level about the life cycle, adding more variety to the game.

I was stuck for quite a while on how to simulate an entire water cycle. I was thinking of simulating temperature warming the land and then the air, causing winds to blow from seas towards land. Eventually, I settled for an easy idea: magical heaters cause water to evaporate and coolers cause clouds to turn to rain. It’s simple and gives level designers and players more control - this is good for puzzles.

I also wasn’t sure what the criteria should be for “water cycle has been established”. I thought about measuring average sea levels and checking that they stay within a range for a period of time. But then, what is the “sea”? Is a puddle “sea”? Is underground water “sea”? Eventually, I settled on the criteria of keeping a rate of conversions above a threshold, eg. X water tiles need to be converted to steam and Y of steam back to water during a period of time. I think this was a nice solution.

The game houses an in-game editor. It became essential to be able to create levels. Players can also create their own levels. It shares a lot of code for playing the levels and can be used as a sandbox mode for just messing around. For a lot of games, you will absolutely need an editor of some sort. There are arguments to be made for an in-game editor that you can just immediately start playing in. But implementing it is a time investment.

Outside of the game design part, the implementation itself went

mostly smoothly. The game is written in C++ using SDL2. I wrote about my

setup for SDL2 here. I only had a

single .cpp file (main.cpp), which included

all the headers. Headers did not require include guards and everything

was defined and declared in the same place. This approach is

unconventional, yes, but it worked well for this small solo-dev project

and saved on precious time.

C++ annoyed me in several ways. I used global compile-time constants

(but not global variables). I went through some trial-and-error to be

able to initialize my std::arrays with template arguments

omitted. It was also picky about which of my structs and classes it

considered constexpr-able. I’m sure it all makes sense if

you’ve read the standard, but for simple coding, it was just a hurdle to

get over. std::string and std::vector are

supposed to be constexpr-able as of C++20, but I could not

get that to work and did not bother too much - arrays and

char[]s were good enough for me!

I made good use of asserts and

static_asserts, which are great if you’re running on time

and won’t be writing tests. Those were especially useful for in-code

reminders on all places I need to update when adding new elements (eg.

water, stone, mud).

So I can’t say C++ is bad. It’s a performant, well-supported lanuage

and I was surprised I was able to have the game run at 60 FPS with very

few optimizations. The main one was rendering grid tiles onto an

SDL_Surface first and then converting it to a texture. It

turns out that making render calls for filling tens or hundreds of

thousands of rectangles each frame is going to be slow, who would’ve

thought?

There is an FPS counter implemented using

SDL_GetPerformanceCounter(). How to implement it is a topic

I’ll cover in a different post, I think a lot of devs get it wrong.

A good thing about using C++ and SDL2 is that you can easily compile the project to WASM with emscripten. Having a browser build is really important, as a lot of people will pass up on download-only games during the ratings phase of a game jam.

By default, emscripten will embed the game in an HTML template that

includes its logo and some other things you don’t want. I created my

own HTML template and enabled it with --shell-file

for a simpler game embedding.

At first, there were issues running the game in the browser that took

a while to debug. It turned out that my 48_000 tiles of an

int enum and a bool were consuming too much

memory. I changed the underlying enum type to char

(should’ve put int8_t) and moved the bools to

a separate std::vector<bool> object (with bit-storage

optimization). Eventually, I also slapped -sINITIAL_HEAP=128MB

as a compiler argument for good measure.

A limitation of emscripten and WASM is that it generally doesn’t let you mess with the clipboard, for security reasons. This was relevant since the game has a save/load system (also used to save levels from the editor), which can save to the clipboard or a file. I just used pragmas to omit clipboard saving options from the web build.

Save-files were versioned. At first, this was just a simple number 1 at the beginning of the file. Even if you don’t expect you’ll have multiple save-file versions, I strongly advise doing something like this. Provide a placeholder value in your save-files - if your game logic changes so that save-file structure needs to change, increase the number.

Loading a save first loads onto a new state object and, if the load is successful, only then replace the real game state object. Thus, corrupted save-files will still let you keep playing the level you were on.

The game’s UI was at first manually coded with a painstaking amount of manual organizing of elements. After a while, I caved in and replaced it with Dear ImGui. It is a great library for quickly composing UIs!

If I have to say something bad about it, it’s that it doesn’t really

support custom layouts and alignments - you can only stack elements on

top of or next to each other. Also, since it both displays info and

accepts input (button clicks, etc.) and I coded all of it in the input

part of my input-update-render loop, it means that the UI is one frame

behind in the data it shows. Plus, Dead ImGui added ~15s to my compile

times, so I created a separate Makefile rule to compile it to

.obj files and then pull those in, rather than having to

recompile it any time I made a tweak to game code.

Looking back, I’ve spent about a day on the UI and save/load code. Time is a precious resource in game jams and you need to be realistic with what you can and what you should do. The time you save avoiding unnecessary work can go towards polish or adding more variety and levels to your game. Eg. I had plans for ice, fire, and even for electric cables that need to connect generators in a loop jam theme drop, but did not have the time for them.

When people complain about not having enough time, they’re usually really talking about energy. Being realistic with yourself and not spreading yourself thin is good advice. Or, you could be like me and crunch like crazy because you just love spitting out code. All those abstract connections and rails just hit that sweet spot in the brain.

But accept that some code quality will need to be sacrificed. I was

slapping TODOs left and right, using asserts instead of

tests, and restraining my urge to carefully consider the philosophical

implications of making a given function global vs. a struct/class

method.

For most of the jam, I was in the mode of obligatorily implementing one thing after another. It’s like there’s a checklist in your head that you have to go through before getting to the fun part. And the fun part, maybe call it game gardening, is idly looking at your game and gently adding and tweaking whatever seems like the best idea at the time. Sometimes I wonder if gamedev can be done in this “gardener” mode from the very start.

Before the jam, I suggest having a blank template project ready and making sure it runs on your machine and in the browser. Towards the end of the jam, I suggest having a runnable build submitted a few hours before the deadline! Seriously, do not wait for the last hour!

With the game submitted and 4 days passed, it was now time to play and rate the games. I played and rated several, mostly ones that received little attention. It feels good to see your game being played and receiving nice words about it. A lot of games were simple but fun and made me realize that fun games can be made without working yourself too hard.

I also got some feedback on my game. Players thought my take of making a falling sand game for this theme was creative, but it was hard to see what was happening in individual tiles and more levels would’ve been good. That’s fair. I wanted to add more levels, but ran out of time, which was eaten by UI and other work. I also think I chose a hard idea to make. Falling sand games are chaotic and non-deterministic, whereas puzzles tend to be very deliberate around level design.

A lot of people were pushy with trying to get their game noticed. Eg. on Discord, people were offering rate-for-rate and dumping game links in incorrect channels under the guise of questions for help. Meh…

On the other hand, someone on Discord disliked that all their game’s feedback was of the simple “good job” kind and they wanted more criticism to know how to improve. I strive for that level of maturity.

There are a lot of people who like the idea of making their own game, but the undertaking can be gargantuan. I watched YouTubers say how marketing is not important and all you need to do to make it in the indie games industry is create a good game. But then their idea of a good game is an insanely perfected product that few humans are capable of creating and that can measure up against the avalanche of games that’s constantly coming out. It makes you realize just how oversaturated the market has become.

That’s why game jams are great. The time is limited, so you’ll only need to reserve a few days for them and you can just enjoy creating the game you like without the weight of having to “make it”. I don’t know, maybe I’ll participate in another one at some point.